I haven’t watched much of Pedro Páramo on Netflix, but I have watched a lot of what my kids call Pótamo, which is about six minutes of the movie that we have watched, over and over again, together. They ask for it. They love it. It consists of a selected handful of very specific scenes that I have shown them and of which they approve, based on very specific characteristics. They take turns asking for those very specific scenes, by names that have been established, and we watch them, and they flip through the movie that way, unstuck from the tyranny of chronological storytelling. This generation and their short attention spans, etc.

It began haphazardly. We’ve begun exposing them to screentime—TM, must credit Phil Maciak—but because we’re fabulous parents, we’ve mostly been showing them whatever the opposite of Cocomelon might be, slow and luxurious and non-addictive. Along with Sesame Street, because, obviously, a favorite is “California Trains! 1 Hour, 150+ Trains!” which allows us to point out what colors different trains are, and whether the trains are “happy” or “crying,” a Rorschach-y gut judgment whose rubric is inscrutable, but about which they are never uncertain. We have also watched “Scenic train ride from Bergen to Oslo (Norway),” which they enjoyed, but at a certain point Nicanor asked “Where is the train?”

One day, I put on Pedro Páramo. I had started it the night before, and had swiftly been overcome with guilt that while I had begun reading the new translation—of this hypercanonical novel the CIA used to flatten literature that I read two decades ago and have completely forgotten—I hadn’t gotten very far, had put the book aside, and then, after a week or so, I had hit that very specifically cursed point where it had been too long since I’d read the beginning to simply pick up where I had stopped, but also, I had read that part much too recently, and it was still too fresh in my mind, to start reading it again from the beginning. I was therefore overcome by a second-order wave of readers guilt when I started watching the movie: I should really read the book first, right? So I turned that off, too, right after the narrator arrives in Comala and meets a lady in the dark with candles who turns out to be a ghost like everyone else.

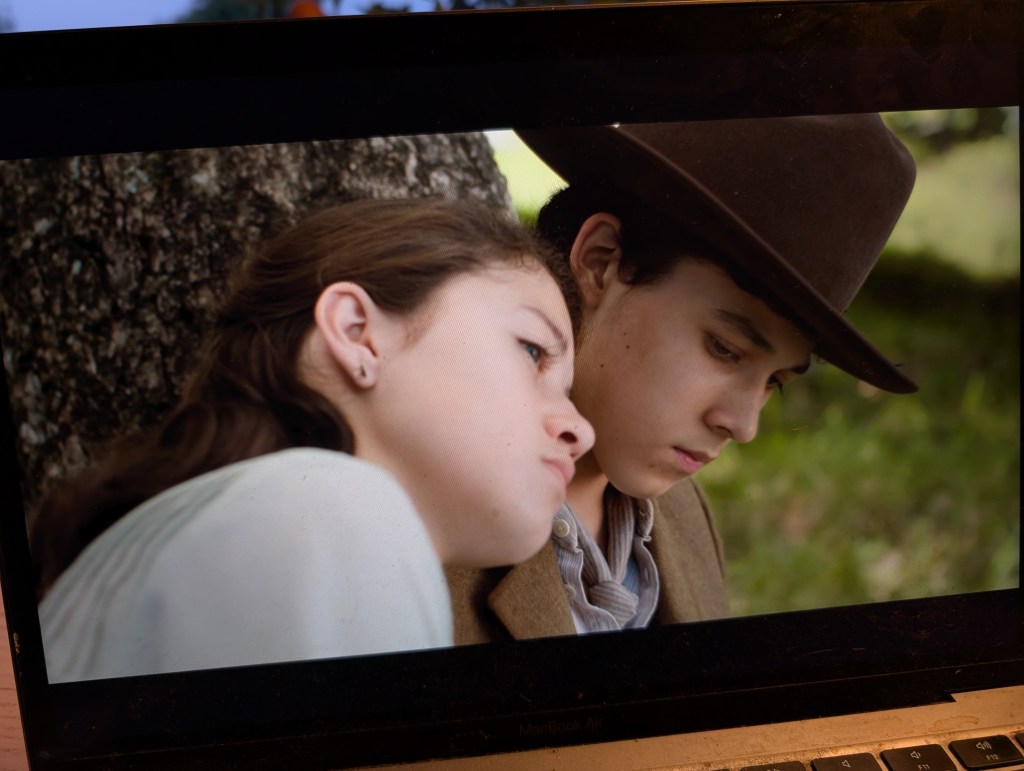

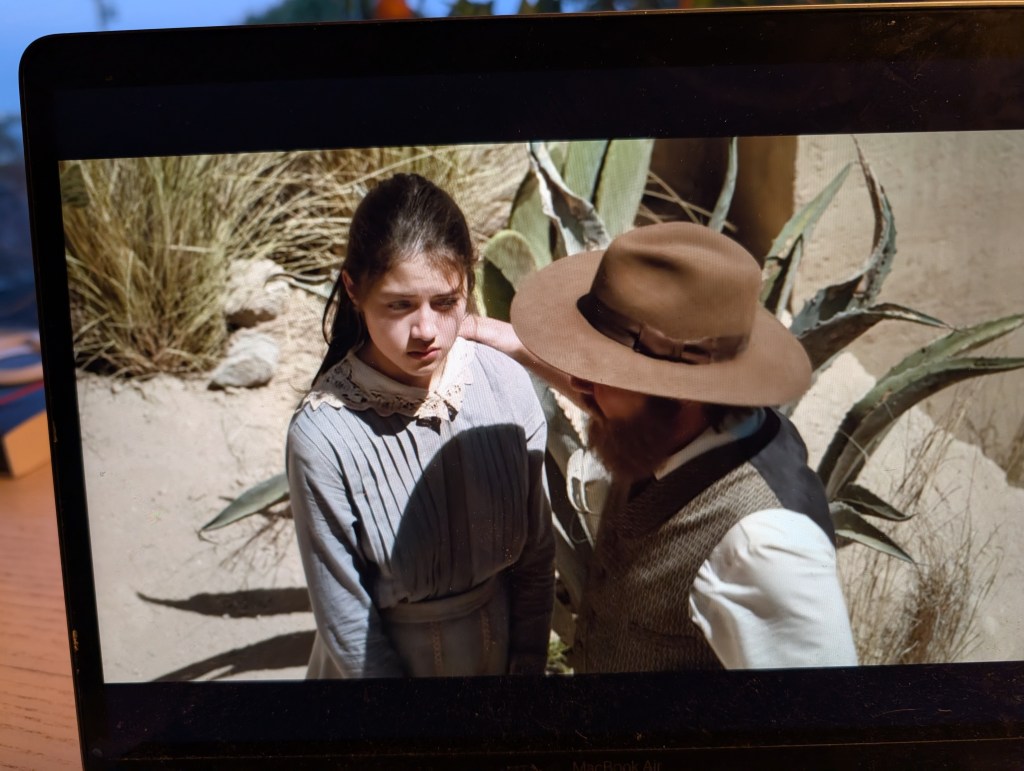

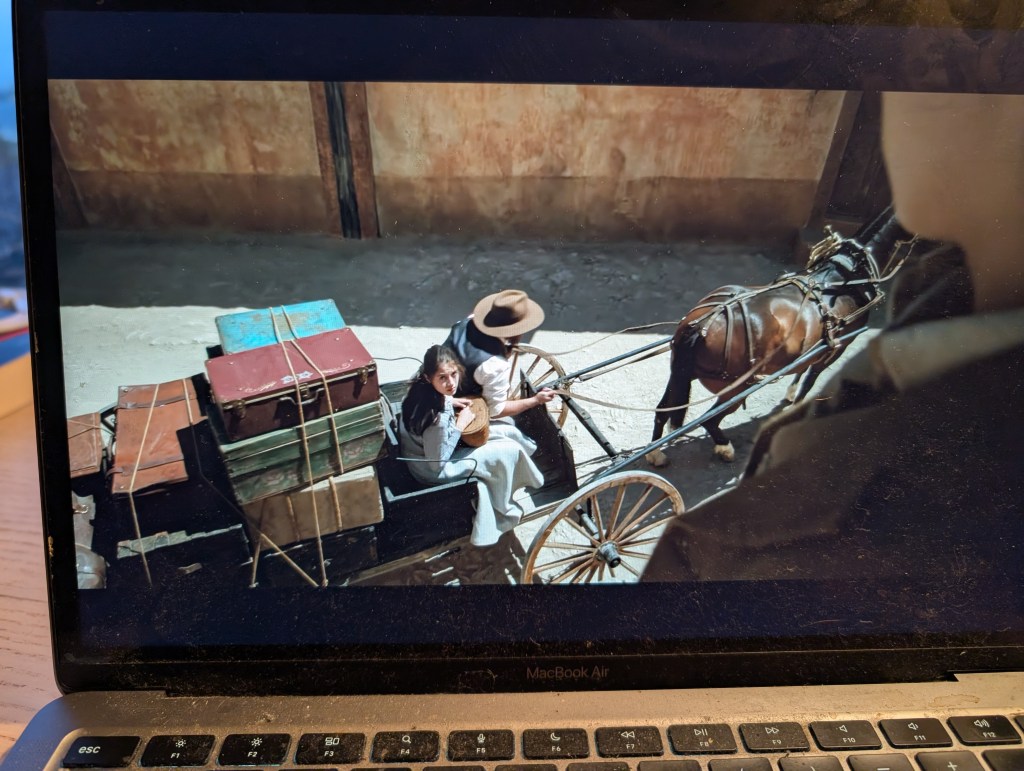

When, on a whim, I turned on Pedro Páramo for the niños, it was already about ten minutes in, where I had stopped, the first flashback to Pedro himself, a boy, in an outhouse, staring out at the rain-dappled leaves in a not-yet-corrupted-and-evil reverie. They were enthralled. It may be that potty-training toddlers are particularly interested in this kind of epic drama, of not-yet-corruption, of idleness, and of sitting and trying to make poop. Or it may simply be that screens have a sorcery over their brains and they are entranced by any kind of pictures and music, helpless against its satanic witchery. It’s one of those two things, but either way, we watched for about four minutes, and then watched it again, and again, and this has been the bulk of the film as they understand it, and as it therefore is:

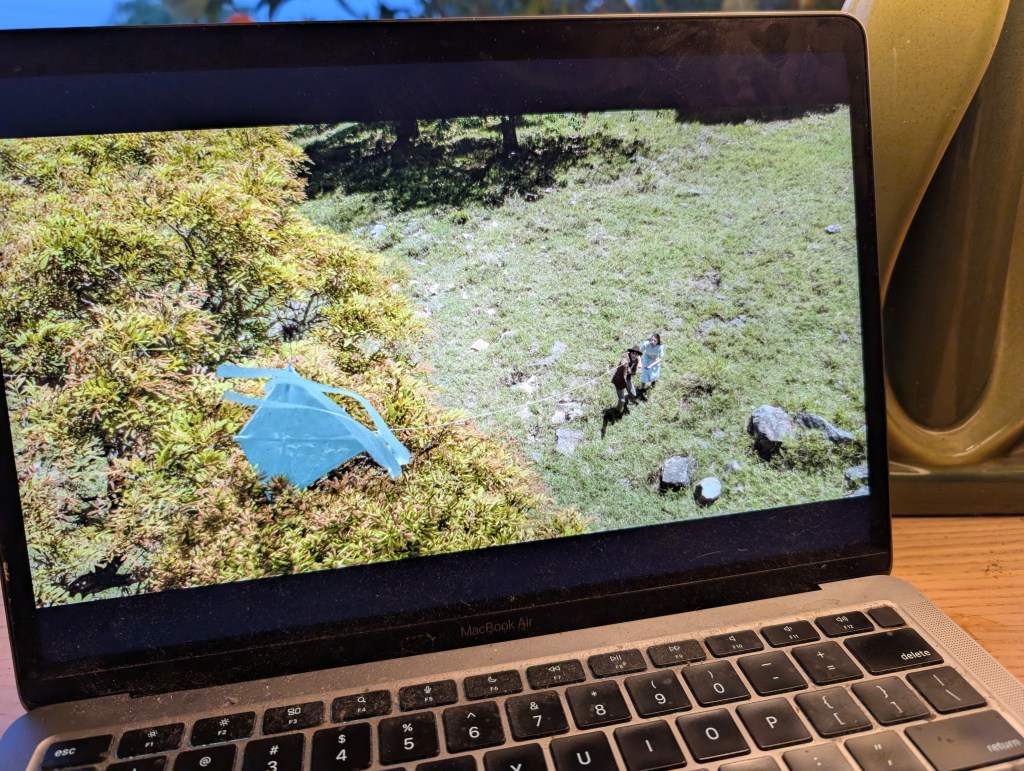

At this point, the movie gets a little bit same-y for a while, mostly candlelight ghost conversations, so we have taken to skipping over a bunch of ghost shit (especially the nudity and the part where protagonist gets sick and dies and is buried) so that we can pick the story back up when it rains. Nicanor loves this part. “Lluvia!” he demands, and so we begin with the green and the rain and the light:

I don’t remember much from when I read Pedro Páramo as a young graduate student. I remember the blue color of the cover, the way the plastic had sort of peeled off of the cover around the corners, and I remember how surprised I was, halfway in, when the apparent protagonist dies and narrates the rest of the book as a ghost among ghosts. I remember thinking: man, Mexican literature is all about ghosts! I remember the feel of the wood of the desks, when we were sitting and talking about the book.

The babies are two and a half, and I’ve already forgotten most of their lives; I forget that they aren’t babies, and what it was like when they couldn’t look and see and talk and ask, when they couldn’t watch a movie and say of what’s happening on the screen “más!” or when they couldn’t ask, with focused concern, “where my poopoo?” after the toilet flushes. They’ll forget everything, in a few years, when all their early childhood memories are wiped, as for some reason happens when kids are 6 or 7. But somehow, somewhere, I’ll remember what it feels like to watch Pótamo, a twin nestled under each arm, absorbed in the light on the grass, the rain, and the comida.

Discover more from and other shells I put in an orange

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.