There’s something almost interesting about how belated and redundant this new “In-N-Out owner bashes Oakland and its police in addressing store closure” story is, as the whole wahala* is taken up again, nearly a year after the closure happened. It began when SF Gate plucked a handful of quotes from a 44-minute PragerU interview with the CEO of In-N-Out—in which the reactionary CEO of a reactionary agitprop content mill prompted her to say that In-N-Out closed their Hegenberger location because of crime, which she dutifully did—and then a day later, the LA Times dutifully printed essentially the same story, followed by the Murdoch Press and then various other bottom-feeders.

Perhaps any kind of slop is good enough to be served during the holiday lull, when these kinds of publications are even more on autopilot than usual. But still, it’s striking how easy it was for PragerU (“a far-right media outlet structured as a non-profit educational institution” and “a central node in the production of misinformation and radicalization in the United States today”) to get some apparently respectable newspapers to dance to their music. Because it’s worth reiterating how stale and thin this “news” really is. When In-N-Out closed its Hegenberger location in January, nearly a year ago, the story, then, was exactly the same as it is now: the company said it was because of crime and the media dutifully said that the company said it was because of crime. It was a big story because crime was a big story in an election year in which progressive politicians in Oakland were specifically and successfully blamed for it. The closure of this single restaurant was even brought up in Barbara Lee’s Senate debate.

If there’s almost something interesting in how literally nothing the CEO said is different than what In-N-Out said almost a year ago, it’s how—when a bunch of newspapers present this information as news, eleven months later—the implication is produced that it really is new. After all, the headlines aren’t “CEO of In-N-Out repeats the thing the COO of In-N-Out said 11 months ago,” after all. Simply by reporting on the fact that she said these things, and by framing these things as newsworthy, that handful of sentences she was prompted to say in a 44 minute interview (that mostly covers “How God Gave Her the Strength to Lead One of America’s Most Beloved Brands”) comes to feel like a new revelation or confirmation of what we hitherto only suspected. We get the impression that this has been a real break in the case. After all, if it wasn’t news, why are we reading it in the news? It must, therefore, be new that crime was the reason the In-N-Out closed. And in this way, it becomes news and the story circulates again.

Was crime the reason the In-N-Out closed? I mean, probably, on some level. In general, when a business closes down, the story that the business tells about its closure is likely not to be the whole truth. A lot of businesses close because their executives made bad decisions, or even committed crimes; businesses go out of business all the fucking time, especially restaurants, but if you’re an executive at a big corporation that’s closing locations, it’s in onwn your self-interest to say something other than “we are closing these locations because we made bad decisions or committed crimes.” And we should just be generally skeptical about anything that corporate PR says, because there job is not to tell the truth. The same people who tell newspapers why they closed a location have the job of advertising how great their business is; it’s in their self-interest to say something other than “our business failed because it was a bad business.” Attractive fictions are what corporate PR is in the business of producing, and when advertisements aren’t lies, they are bullshit, as indifferent to the truth as a PragerU executive. If you think a fast-food restaurant’s PR department is devoted to the pursuit of truth, compare what a cheeseburger looks like in an advertisement to what it actually looks like in your hand.

That doesn’t mean they’re always lying, of course, and in this case, “crime” certainly seems relevant. No one really denies that there were a lot of break-ins at the location. (“A security guard with Brosnan Risk Consultants who patrols the In-N-Out said they see multiple break-ins at the fast-food restaurant daily,” as the SF Standard reported back then; “‘On a regular day, I’d say five,’ the guard said.”) The location was apparently still profitable, but it’s not crazy to assume that this must have affected the well-being of people who worked there. Given that In-N-Out really is something of an outlier in terms of how it treats its employees—worker pay, benefits, and reported satisfaction are unusually good for the industry—I’m willing to say that “for the safety of our associates” feels not totally implausible as explanation for the decision (even if my conspiratorial heart asks questions). But “crime” is at least a credible answer, if “why did this hamburger joint close?” is the important question.

My point is: Is it? Frankly, I couldn’t give a shit. Why would I go to that In-N-Out? Why would I care if it closes? I live in Oakland. The only In-N-Outs I ever go to are one of the six on the 80, on the way to Sacramento, and in that sense, I am amply supplied with opportunities to eat moderately good cheeseburgers and barely passable fries. In-N-Out is not really a destination; it’s a restaurant designed to go to while you are on the way to somewhere else. The clue is in the name: for all its old-fashioned California charm—even if it’s run by Trump donors who do things like give interviews to reactionary agitprop content mills—that In-N-Out was an Exit 36 on I-880 burger, a “you just saw the As or Warriors play and now you’re hungry” burger, or a “you’re almost to the Airport and you don’t want to pay airport food prices” burger”; it was a “solve the problem of being hungry in my car” kind of place. You had and still have lots of other options if that’s the problem you need to solve.

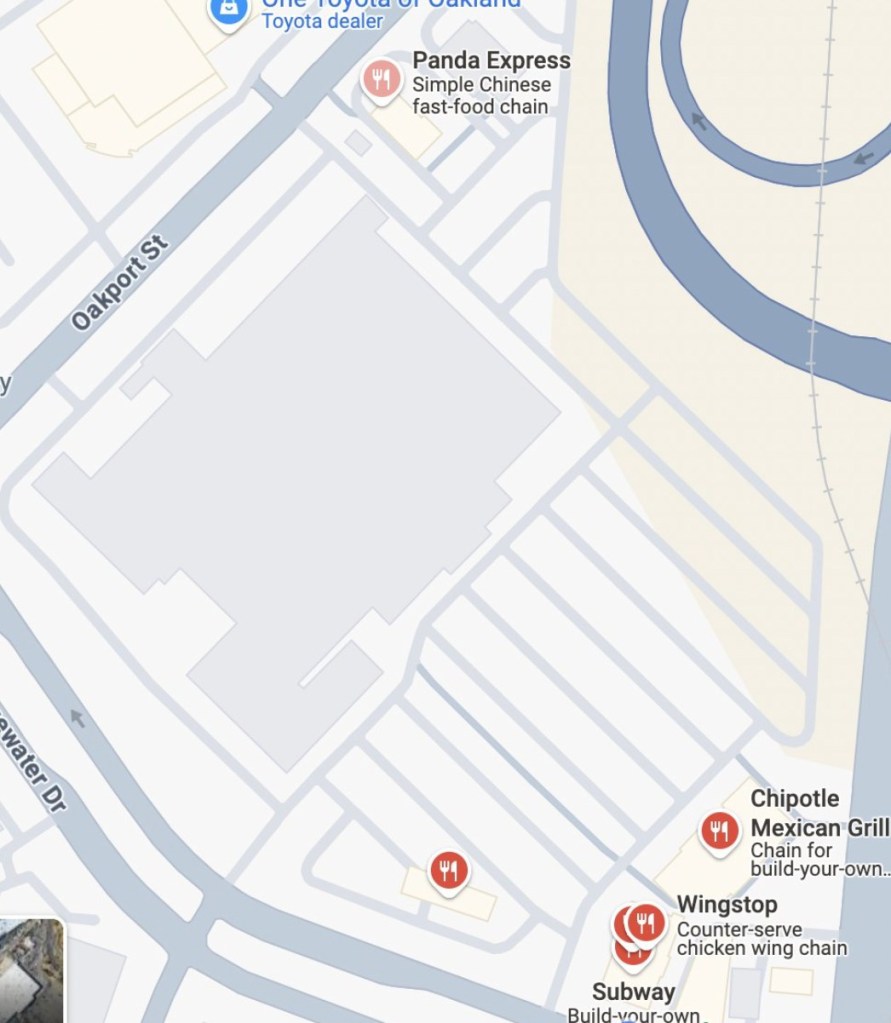

As far as I can tell, none of the salary-drawing journalists at respected newspapers or television channels who have “reported” on this closure have bothered to answer what, it seems to me, would be an interesting and obvious question: how is it that at the same basic location, you could then, and can now, eat at the following chain restaurants: Chipotle, Round Table Pizza, Dunkin Donuts, Subway, Wingstop, Raising Cane’s, and Panda Express? There’s even a Jamba Juice. They all share the same parking lot and 880 exit, and, presumably, the same crime problems. Why haven’t they closed? If one fast food restaurant closing is news, why isn’t half a dozen not closing, at exactly the same location, also a story?

I’m being rhetorical, of course. “In-N-Out closes because of crime” wasn’t “news” because it was a new thing that had just happened (otherwise “Still-closed In-N-Out is still closed for the same reasons as before” wouldn’t have been “news” either). It was “news” because CRIME IS BAD IN OAKLAND is a story that people—like the CEO of PragerU—want to tell. If the story of why there are so many restaurants at this single crime-ridden location is less compelling, perhaps it’s because the most plausible answer is that the owners of those restaurants don’t give a single solitary shit about their employees’ well-being, because those are all still profitable restaurants. If the In-N-Out is actually the weird outlier—in closing a profitable location because of its employees’ well-being—perhaps this is not the story PragerU wants to tell, just like no one at these publications seems interested in devoting any time and energy to figuring it out.

It’s also not hard to figure out. There are so many restaurants here because the parking lot these restaurants are clustered around is right off the 880 freeway. There is virtually no foot traffic—because the entire Hegenberger corridor is basically just parking lots and big roads and people passing through, such that there are lots of hotels and other such establishments here that you might drive to on your way to somewhere else—but this little cluster is where you might find yourself, if you are passing through on your way to somewhere else. It is, in that sense, anything but surprising that enterprising thieves focus on this area. There are lots of people passing through—perhaps in rental cars filled with luggage—and not so many people who aren’t. If a company was, for example, happy to take your money and indifferent to your car getting smashed while they were doing so, they might be happy to continue to have a location here.

One reason they’re all at this particular parking lot—rather than another—is that there used to be a Wal-Mart here, and the restaurants initial popped up around its gravitational field, an actual draw for customers. It closed in 2016—before “progressive politicians killed Oakland business with crime” was a media template, so there was no such story about it—but once you’ve established a cluster of fast-food restaurants just off the freeway, inertia keeps them in the same place, even if the now-empty Wal-Mart building is why they were originally clustered here. There will still be a steady flow of customers who see this sign and say “you know what? I could go for something to eat” and when they do, this is the exit and turnoff they will take.

And so it goes. If crime follows blight—as the unkillable “broken windows” hypothesis declares—then the Wal-Mart closing would be the number one suspect for why crime is bad at this location. And one might imagine that a department of police officers whose goal was to catch criminals would have been able to use the information that people are constantly committing crimes here to catch them and imprison them, but such a person might not be familiar with the Oakland Police Department, who do not generally seem to view this to be their job, even to regard being asked to do this as an absurd imposition on their real job (sitting in their cars collecting overtime).

An almost more interesting question than “why did this hamburger close?” is “Why is ‘why did this hamburger joint close?’ still an important question?” In August, after all, a downtown Shake-Shack closed, and everyone got very excited about it, and instantly said all the things they had said when the Hegenberger In-N-Out closed. They said this because we were at that time only a month and change away from a recall election in which our mayor and county DA would, as it happened, be recalled. And so, pundits made a big deal out of what might, otherwise, seem like not a very big deal at all: “Crime and the failure to police it is robbing a whole community of countless goods most people in Oakland value,” declared this fucking dude; “The burger chains are a symptom of this illness and not the most important symptom. The mayor, police chief, and county da should all feel ashamed.”

Even someone as smooth-brained as Conor Friedersdorf has to admit that, taken on its own, a burger joint closing is not actually a big deal. But all the articles about that Shake Shack closing—and there were articles about it, in big important newspapers—made a point of connecting the dots, noting that the closure “comes as other businesses in the city’s downtown area and Hegenberger corridor are struggling to stay open or have closed their doors altogether.” Look at the big picture! Symptom of an illness. Be ashamed, Oakland! Always-Sunny meme!

The funny thing is that the Shake Shack in question had already been closed for a month before anyone in the media heard about it; presumably someone at SF Gate read “Shake Shack to close 9 underperforming restaurants” in Nation’s Restaurant News, a month later, and dug a local angle out of an already shuttered location. But no one had noticed that Shake Shack was closed, because it couldn’t possibly matter to anyone; it was “underperforming” because people weren’t eating there. And why would they be? I had been to that Shake Shack once, as it happened, but I wasn’t about to go a second time. It was not a nice place: you had to order through a machine, you couldn’t really sit down anywhere—and didn’t want to—and more to the point, it was just a fucking burger. According to google maps, The Melt is 0.2 miles away from that location (solid grilled cheese), Trueburger is 0.3 miles (to demonstrate what a truly great cheeseburger tastes like), and also BigE burgers and Lovely’s are 0.4 miles. But if you’re ordering a chain cheeseburger in that area, what’s wrong with you. Live your wild and precious life and eat at Shawarmaji, Xolo, or Sisig, at least. Personally, I would have hiked the half-mile to Fresh and Best II or Golden Lotus because I prefer to live in truth.

***

However: If you’re going to make a destination out a Hegenberger cheeseburger, may I suggest taking a bike ride and hitting up Hegenburger?

I mean, look at this fucking signage:

You should bike there because the way to get there is to thwart thieves is by not having a car. Can’t break windows that don’t exist! CHECKMATE, BIPPERS.

From Jack London, it’s about a 42-minute bike ride along the bay trail that even most east bay folks probably aren’t that aware of, but, especially once you’ve cleared Alameda, it’s a surprisingly bucolic stretch of very empty post-industrial regrowth. Much of it is not all that well maintained, but it’s also not very worn, and there’s lots of stinky organic bay air to breathe as you coast along. It’s shockingly pretty and calm, on days when the weather is these things.

The first part goes along the estuary and is gentle off-street biking until you pass the coast guard island and Union Point park, at which point you have to take E 7th for a bit until you get to Fruitvale avenue; there’s a another short little stretch of bike trail between the two bridges to Alameda, and for a long time that’s as far as I thought you could comfortably bike (also, I would usually go over the bridge and fuck around in Alameda at that point, since there are lots of nice estuary bike trails gentle streets that take you to shitty hot dog spots and whatnot). Especially if you bike across Alameda to the old Naval base, which is now just endless water views and concrete paths, interspersed with implausible vodka distilleries and the occasional food truck—and you have to bike all the way across Alameda because, while technically you can bike through the Webster Street Tube from Jack London, the thing about doing that is that you will inhale enough exhaust to find yourself essentially intoxicated, and not in a good way, on the other side—you wouldn’t necessarily think to keep heading down the bay trail, or at least I never had.

And then one day I had to pick up our ancient, once-luxury vehicle that had been serviced, and discovered—like a modern day Gaspar de Portolá—that San Leandro Bay is not only a thing, but is ringed with bike trails and little sparsely occupied shoreline parks, and if what you want, more than anything in the world, is to access the deliciousness of a cheeseburger in that beautiful industrial crotch formed where the freeway meets the airport meets the estuary, you can patronize Alan Liang’s shitty hamburger place—and don’t worry, he’s also mad about Oakland progressives—at which point, in my opinion, the best move would be to bike the rest of the way down to Oyster Bay regional shoreline, where you can watch the planes take off and eat your hopefully still warm French fries and cheeseburger in blissful solitude.

Discover more from and other shells I put in an orange

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.