Am basically better. And when I was telling someone about this experience, they very pertinently observed something like “they should have had me come in and get tested.”

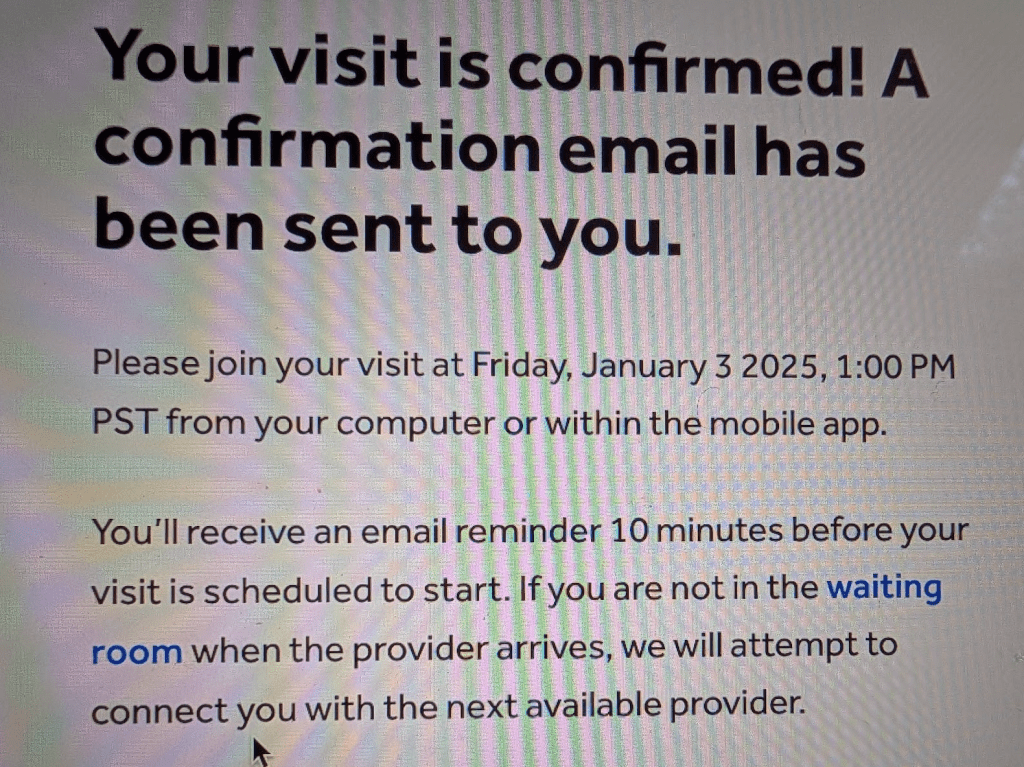

It’s a really interesting statement, because it’s absolutely true—and when zoom doctor #2 was walking me through the various forms of diagnostic protocols that have been developed, it was pretty obvious “go in and be examined by a real doctor, in person” was absolutely the right thing to do, and not even all that complicated a proposition—but the reason I didn’t do that, even if the “should” was clear, was that there was not really an “they” in this entire process. I had sent a message to my regular doctor and they replied, basically, that they didn’t have any short-term appointments, so, you know, we advise that you get someone else to fix this. So I did: I logged on to a virtual urgent care service and (eventually) got a doctor who would give me whatever I asked for, someone with Medical Authority who would, nevertheless, basically loan it to me and write what I told him to. It was a little like when you need someone to write a letter of recommendation for you and they make you write it for them.

Anyway, it made me reflect on the absence of a “they” to make you do the things you still “should” do, the way the should imperative survives the degradation and absence of the “they” (which our brains—and the material system we’re embedded in—refuse to admit). Doctors and medicine still have all this authority and social power, such that you can’t get penicillin without a doctor’s say-so, in this baroque antiquated system where the doctor just, like, calls or even faxes the pharmacy. But because it’s become so hard to actually access timely care, we have online urgent cares as a workaround.

Maybe things like penicillin should just have a lower threshold to access? I’ve been to countries where a lot more medicine is over the counter than in this country. But it’s like we’ve built high and formidable walls around the castle entitled “medical prescriptions,” and then it turns out that too many people need to access that castle, so instead of re-doing the main gate, they just built a tunnel under the walls so that people can get in and out when they need to, if they really need to. Sort of defeats the purpose of the walls! But of course, the real problem is that there aren’t enough (or enough access to) “they”s who you can talk to about basic things in a timely way, and we jerry-rig a system out of the fact that there aren’t, but people still need access to what those “they”s still control. Obviously, the way it should have worked is that I should have been able to access my regular doctor, or her team; care should be as 24/7 as need, but because of neoliberal capitalism (etc) it isn’t, so we have this.

And this is a success story, too! I got the prescriptions, took them, and basically feel better now. But at every stage of the process, the feeling was: this is a super weird process no one would have intentionally designed, and didn’t, but to which we still donate our general social observance of authority, because, you know, we need the eggs.

Now the real ethical dilemma is this: do I still go to the other pharmacy and pay two bucks for a bottle of penicillin, just to have it for when the zombie apocalypse happens? Probably, right? But that’s exactly the problem and feeds into the kinds of scenarios where we lose antibiotics altogether (in some ways a more terrifying scenario than zombies).

Discover more from and other shells I put in an orange

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.