Remembering that there is no meaning in the world unless we put it there, by our choices—and that without taking action, and without pushing (with moral force) our subjective will into an uncaring and absurd world, freedom is ultimately meaningless—I decided to go to Berkeley Bowl at 4 pm of a Sunday afternoon.

If you know, you know, and if you don’t, now you do: It’s not just that it’s crowded then, though that is of course exactly the problem. It’s that, like a lot of east bay infrastructure built decades ago for a certain amount of people, and now supporting too many more than that, the Berkeley Bowl’s aisles and lines, and especially its parking lot, become morally unpleasant to navigate. Just as cars alienate you from your environment, making you hate and struggle with your natural comrades among the masses of the world—instead of uniting with them against your common oppressors, the capitalist class—your massive-ass shopping cart does not fit in the spaces through which you must navigate it, if there are other people in those spaces, with their own massive-ass carts. You will not die, there, most likely, if you go to Berkeley Bowl at 4 pm of a Sunday afternoon, but you will get angry at the other people around you, who will get angry at you—and you will suppress that anger into a nugget of hate, festering in the core of your immortal soul—and all of this is a hazard far more serious than the mere risk that your cart will bump into another cart, or that you will give way and wait for the other person to go by, or whatever fate it is you are trying to avoid when you save yourself a second by passing a stopped cart, or go first instead of giving way. You will be unbraided from the divine singularity of the universe; you will find yourself departing from God, and demanding to know why He has abandoned you.

(A propos of nothing, my mother was a very slow and erratic driver, and I am too, but in my mind I’ve rendered into moral superiority what was, with her, the sort of terrifying experience of sitting in a car she was piloting all around the lane, apparently at random, while driving 10-15 percent slower than the cars around her, who zoomed past without her apparently noticing their rage—which as a kid, would drive me crazy—but for me, now, not a kid, I think to myself: look, if I go slower than other cars I will arrive, what, a minute later? Two minutes? I will arrive when I will arrive, why have the arrogance to believe that we can control time? Let justice be done though the heavens fall. And of course that must have been how she thought about it too, if she did; the zen state which I’ve achieved so laboriously may have come more naturally to her, a parent, or perhaps that is the idealizing ignorance of a child; maybe it came as hard for her as it has for me, now, also a parent.)

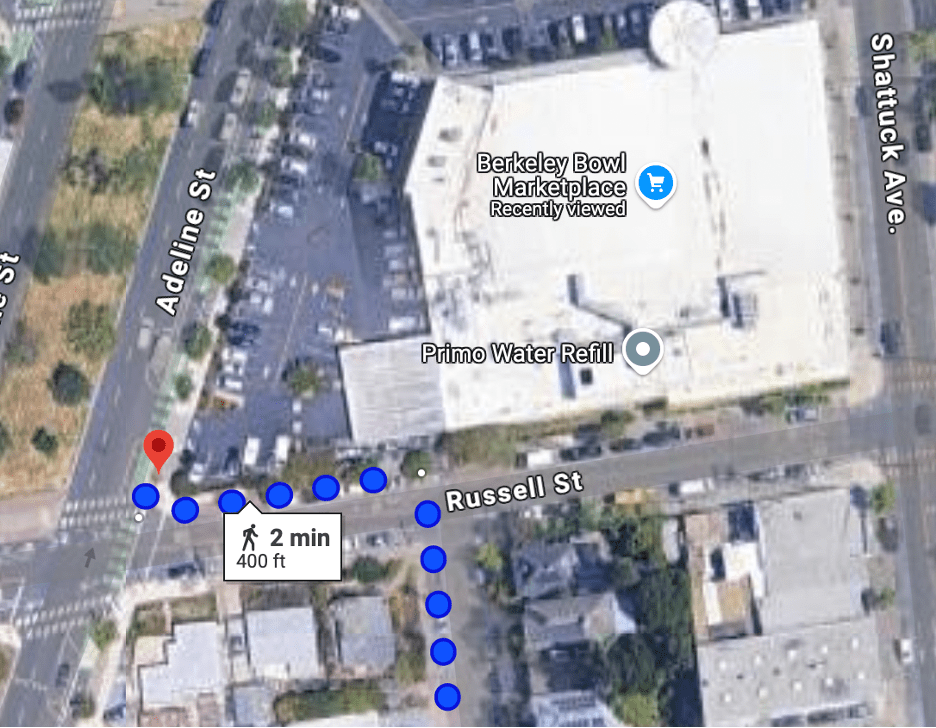

I didn’t park in the parking lot, that was my first breakthrough. Avoid that whole mess: park on Newbury street, close to the intersection with Russell (where there is also a lime and lemon tree, within easy reach, should your ethical system allow you make use of its bounty). There is an opaque plastic fence running along Russell, where employees can eat lunch or take their breaks and be unseen by all the maniacs in the parking lot itself, such that when you walk around it into the parking lot, at the far end, there will likely already be a grocery cart there waiting for you—which an employee will attempt to take from you, not understanding that you are piloting it into the store itself—and there, you will find that not parking in the parking lot itself has already made it possible to avoid a substantial percentage of the bruising your raw immortal spirit would otherwise have received (as long as you acquire no more than the number of bags you can carry the 400 feet or so).

Grocery stores, all of them, produce a numinous, out of body experience: there is too much here, far too much, and yet that superfluity, that excess, can actually be experienced in the most embodied, corporal way: you simply can’t eat all of it. It will take all of us, as a society—including the guy you see, with a dog, rooting through the back dumpsters—to turn all of these dead (and dying) plants and animals, all carefully and laboriously arranged on shelves and cases and in boxes and bags, back into human sufficiency with our teeth and stomachs. But it’s overwhelming! It’s not like opening your refrigerator and deciding what you have and what you need to go out into the world to get (as I did, when I decided to go to the Berkeley Bowl to get the makings of a white person pad thai, that my refrigerator lacked): walking into a grocery store is an experience of such an awful, obscene surplus of possibility that you are thrown back on the resources of the entire human race to cope with it. We will all need to work together to eat all this food, my god. Those are just too many raspberries. At a certain point, even my children would lose interest and stop eating them.

You’ll lose track of the experience in the same way, as the thread connecting it all together will be torn and like recalling a car accident, after the fact, all you’ll have will be the strange stillness of individual instants, each traumatically lodged in the eternity of that memory. Maneuvering around the herbs to get to the greens—there’s something weird about the geometry of that turn, that three other carts moving in the other direction really brings out—and passing the peanuts (we still have some at home), but grabbing a surprisingly cheap bag of oranges, and also the smallest hardest little avocadoes—since the big glorious ones we get from Costco are so rich and massive that we end up wasting a lot of them, when making avocado toast for the kids—and then, the main event: the aisle where you wanted to get tofu and rice noodles, and that couple had left their cart in front of the noodles, so you got the tofu, and had to wait for them to notice so you could get the noodles, too (which turned out to be strangely filled with mortal peril (“Warning: Cancer and Reproductive Harm”????), and because you were waiting, somehow, illogically, that made you feel more rushed, as if you had less time, and so instead of mucking around with tamarind and fish sauce and dark soy sauce and regular soy sauce and vinegar and chilis and whatever else you mix together to make that lovely sauce that makes it taste like that, that you saw someone mix together in a tiktok that made it look so easy, if you only had all those ingredients, and you went to Berkeley Bowl to get them, because if any place had all of them, certainly, wouldn’t it be old union-busting Berkeley Bowl? And it’s true, and maybe that very decision—not to go to Pacific East mall, say, or a market in Oakland Chinatown, but to go to the place where white people can always get their “global” products—was what sowed the seeds of my split-second choice, in that moment, to instead, grab a jar of “Blue Dragon Pad Thai Sauce,” and to decide that it would be fine, and now, typing it on my computer the next morning, I just remember making that decision, even though the whole reason to go to Berkeley Bowl had been to get the actual individual ingredients, not a pre-made sauce blend.

And then home, and I had purchased a lime, a single lime, and so I didn’t harvest anything from that lime and lemon tree on Russell and Newbury, and when I cooked it all together, I foolishly threw the tofu and greens in the peanut oil before the onions and garlic and ginger, but it was ok, I just cooked it on low a little longer, with some soy sauce and water to mix the flavors, and in the event, the Blue Dragon Pad Thai Sauce was not bad, really, even though it wasn’t what I had been looking for, I remembered to do the eggs last—and the peanut and bean sprouts on top, cold—and I haven’t mastered mixing the rice noodles into the pad thai “stuff” but you can leave that to the eater to manage, it turns out to be manageable. It turns out to be a thing that, when cooked, you can eat, and you do.

Discover more from and other shells I put in an orange

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.